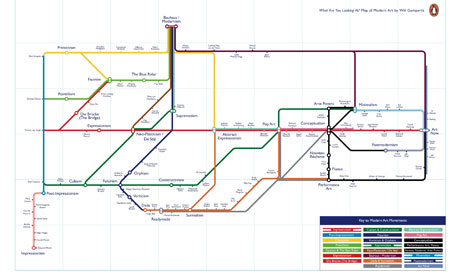

Will Gompertz's tube

map-style guide to modern art movements. Photograph: Viking/Penguin

The story of modern art is in many ways the story of the 20th century. Art shaped and was shaped by events, people, ideas and innovations far beyond the narrow confines of its world. The modern skyscrapers of Manhattan, TS Eliot, Monty Python, the Sex Pistols, the iPhone and the great political, philosophical and social movements of the last hundred years all owe something to the art produced by Manet, Monet and those pioneering artists who followed in their wake.

As does Harry Beck's Tube Map (1931), which I have parodied to illustrate the interconnectivity between many of the modern art movements and their main protagonists. The map is devised to give equal weight to each movement and artist, which is about as accurate as Beck's geographical representation of London: it is a necessary case of form following function. In truth, like all stories, there are lead players, support acts and a few walk-on parts. Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Kasimir Malevich and Jackson Pollock were all, of course, disproportionately influential. As were a number of those on the money side of things, including Paul Durand-Ruel (impressionism), Peggy Guggenheim (abstract expressionism) and Leo Castelli (pop art).

But there is perhaps one person above all others whose influence and personality dominate 21st-century artistic activity and critical thinking – an individual who was able to impose his will on the world without recourse to courting the media, becoming a celebrity, or having vast amounts of money. It is an incredible story within a story that starts on 2 April 1917; on this day, the American president, Woodrow Wilson, was on his feet in Washington DC urging Congress to make a formal declaration of war on Germany – a historic and world-changing moment.

Meanwhile, in New York City, three well-dressed, youngish men had emerged from a smart duplex apartment at 33 West 67th Street and were heading out into the city. They were oblivious to Wilson's exhortations, just as they were to the fact that their afternoon stroll would also have epoch-making consequences on a global scale. Art was about to change for ever.

The three friends walked and talked and smiled, occasionally breaking into restrained laughter. For the elegant Frenchman in the middle, flanked by his two stockier American companions, such excursions were always welcome. He was an artist who had not yet lived in the city for two years: long enough to know his way around, too short a time to have become blasé about its exciting, sensuous charms. The thrill of walking southwards through Central Park and down towards Columbus Circle never failed to lift his spirits; the spectacular sight of trees morphing into buildings was, to him, one of the wonders of the world.

The trio ambled down Broadway. As they approached midtown the sun disappeared behind impenetrable blocks of concrete and glass, bringing a spring chill to the air. The two Americans talked across their friend, whose hair was swept back exposing a high forehead and well-defined hairline. As they talked he thought. As they walked he stopped. He looked into the window of a store selling household goods and raised his hands, cupping his eyes to eliminate the reflection in the glass, revealing long fingers each of which was crowned with a perfectly manicured nail.

The pause was brief. He moved away from the storefront and looked up. His friends had gone. He glanced around, shrugged, lit a cigarette and crossed the road – not to find his companions, but to seek the sun's warmth. It was now 4.50pm, and a wave of anxiety washed over the Frenchman. Soon the stores would be closed and there was something he desperately needed to buy.

He walked a little faster. Someone shouted his name. He looked up. It was Walter Arensberg, the shorter of his two friends, who had supported the Frenchman's artistic endeavours in America almost from the moment he stepped off the boat on a windy June morning in 1915. Arensberg was beckoning him to cross back over the road, past Madison Square and on to Fifth Avenue. But the notary's son from Normandy had tilted his head upwards, his attention focused on an enormous concrete wedge. The Flatiron Building had captivated the French artist long before he arrived in New York, an early calling card from a city that he would go on to make his home.

His initial encounter with the high-rise building had come when it was first built and he was still living in Paris. He had seen a photograph of the 22-floor skyscraper taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1903 and reproduced in a French magazine. Now, 14 years later, both the Flatiron and Stieglitz, an American photographer-cum-gallery owner, had become part of his new-world life.

Arensberg called again, this time with a little frustration in his voice. The other man in their party laughed. Joseph Stella was an artist too. He understood his Gallic friend's precise yet wayward mind and appreciated his helplessness when confronted by an object of interest.

United again, the three made their way south until they reached 118 Fifth Avenue, the retail premises of JL Mott Iron Works, a plumbing specialist. Inside, Arensberg and Stella chatted, while their friend ferreted around among the bathrooms and doorhandles that were on display. After a few minutes he called the store assistant over and pointed to an unexceptional, flat-backed, white porcelain urinal. A Bedfordshire, the young lad said. The Frenchman nodded, Stella raised an eyebrow, and Arensberg, with an exuberant slap on the assistant's back, said he'd buy it.

One of Duchamp's recreations of the original 1917 readymade, Fountain.

Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

One of Duchamp's recreations of the original 1917 readymade, Fountain.

Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

They left the store. Arensberg and Stella called a taxi while the quiet, philosophical Frenchman remained on the sidewalk holding the heavy urinal. He was amused by the plan he had hatched for this porcelain pissotière, which he intended to use as a prank to upset the stuffy American art crowd. Looking down at its shiny white surface, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) smiled to himself: he thought it might cause a bit of a stir.

Duchamp took the urinal back to his studio, laid it down on its back and rotated it 180 degrees. He then signed and dated it in black paint on the left-hand side of its outer rim, using the pseudonym R Mutt 1917. His work was nearly done. There was only one job remaining: he needed to give his urinal a name. He chose Fountain. What had been, just a few hours before, a nondescript, ubiquitous urinal was now, by dint of Duchamp's actions, a work of art.

At least it was in Duchamp's mind. He believed he had invented a new form of sculpture: one where an artist could select any pre-existing mass-produced object with no obvious aesthetic merit, and by freeing it from its functional purpose – in other words making it useless – and by giving it a name and changing its context, turn it into a de facto artwork. He called this new form of art a readymade: a sculpture that was already made.

His intention was to enter Fountain into the 1917 Independents Exhibition, the largest show of modern art that had ever been mounted in the US. The exhibition itself was a challenge to America's art establishment. It was organised by the Society of Independent Artists, a group of free-thinking, forward-looking intellectuals who were making a stand against what they perceived to be the National Academy of Design's conservative and stifling attitude to modern art (just as the impressionists had done in a very similar fashion over 40 years earlier).

They declared that any artist could become a member of their society for the price of $1, and that any member could enter up to two works into the 1917 Independents Exhibition as long as they paid an additional charge of $5 per artwork. Duchamp was a director of the society and a member of the exhibition's organising committee. Which, at least in part, explains why he chose a pseudonym for his mischievous entry. Then again, it was Duchamp's nature to play on words, make jokes and poke fun at the pompous art world.

The name Mutt is a play on Mott, the store from which he bought the urinal. It is also said to be a reference to the daily comic strip Mutt and Jeff, which had first been published in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1907 with just a single character, A Mutt. Mutt was entirely motivated by greed, a dim-witted spiv with a compulsion to gamble and develop ill-conceived get-rich-quick schemes. Jeff, his gullible sidekick, was an inmate of a mental asylum. Given that Duchamp probably intended Fountain to be a critique of greedy, speculative collectors, it is an interpretation that would appear plausible. As does the suggestion that the initial R stands for Richard, a French colloquialism for moneybags. With Duchamp nothing was ever simple; he was, after all, a man who preferred chess to art.

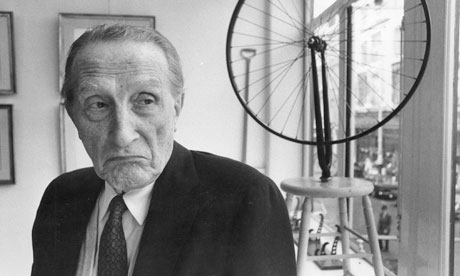

Marcel Duchamp photographed in 1968 with his work Bicycle Wheel.

Photograph: Hulton Getty

Marcel Duchamp photographed in 1968 with his work Bicycle Wheel.

Photograph: Hulton Getty

Duchamp had other targets in mind when selecting a urinal as a readymade sculpture. He wanted to question the very notion of what constituted a work of art as decreed by academics and critics, whom he saw as the self-elected and largely unqualified arbiters of taste. His position was that if an artist said something was a work of art, having influenced its context and meaning, then it was a work of art, or at least demanded to be judged as such. He realised that although this was a fairly simple proposition to grasp, it would revolutionise art if accepted.

Until this point, the medium – canvas, marble, wood or stone – had dictated to an artist how he or she could go about making a work of art. The medium always came first, and only then would the artist be allowed to project his or her ideas on to it via painting, sculpting or drawing. Duchamp wanted to flip the hierarchy. He considered the medium to be secondary: first and foremost was the idea. Art could be constructed from, and mediated through, anything. That was a big idea.

The hidden meanings contained within Fountain don't end in Duchamp's wordplay and provocation. He specifically chose a urinal because as an object it has plenty to say, much of it erotic, an aspect of life that Duchamp frequently explored in his work. It doesn't, for example, take much imagination to see its sexual connotations when presented upside down. That allusion may or may not have been understood by those who sat alongside Duchamp on the organising committee; either way his co-directors were unimpressed. Fountain was rejected and banned from the 1917 Independents Exhibition. The feeling among the majority of the society's directorate (there were some, including Arensberg and Duchamp, who argued passionately in its favour) was that Mr Mutt was taking the piss.

Which of course he was. Duchamp was challenging his fellow society directors and the organisation's constitution, which he had helped to write. He was daring them to realise the idea that they had collectively set out, which was to take on the art establishment and the authoritarian voice of the conservative National Academy of Design with a new liberal, progressive set of principles. The conservatives won the battle, but as we now know, spectacularly lost the war. R Mutt's exhibit was deemed too offensive and vulgar on the grounds that it was a urinal, a subject that was not considered a suitable topic for discussion among America's puritan middle classes. Team Duchamp immediately resigned from the board. Fountain was never seen in public, or ever again. Nobody knows what happened to the Frenchman's pseudonymous work. It has been suggested that it was smashed by one of the disgusted committee, thus solving the problem of whether to show it or not. Then again, a couple of days later, at his 291 gallery, Stieglitz took a photograph of the notorious object, but that might have been a hastily remade version of the readymade. That too has disappeared.

But the great power of ideas is that you cannot uninvent them. The Stieglitz photograph was crucial. Having Fountain photographed by one of the art world's most respected practitioners, who also happened to run an influential gallery in Manhattan, was important. It was an endorsement of the work by the avant garde, and provided a photographic record: documentary proof of the object's existence. No matter how many times the naysayers smashed Duchamp's work, he could go back down to JL Mott's, buy a new one and simply copy the layout of the R Mutt signature from Stieglitz's image. And that's exactly what happened. There are 15 Duchamp-endorsed copies of Fountain to be found in collections around the world.

When one of those copies is put on display it is weird to see people taking it so seriously. You see hordes of earnest exhibition visitors craning their heads around the object, staring at it for ages, standing back, looking at it from all angles. It's a urinal! It's not even the original. The art is in the idea, not the object.

The reverence with which Fountain is now treated would have amused Duchamp, who chose it specifically for its lack of aesthetic appeal (something he called anti-retinal). The original readymade sculpture was really only ever intended as a provocative prank, but has gone on to become perhaps the single most influential artwork of the 20th century. The ideas it embodied directly influenced several major art movements, including dada, surrealism, abstract expressionism, pop art and conceptualism. Duchamp is unquestionably the most revered and referenced artist among today's contemporary artists, from Jeff Koons to Ai Weiwei.

Ai Weiwei's Forever. Photograph: Ren Zhenglai/XinHua/Xinhua

Press/Corbis

Ai Weiwei's Forever. Photograph: Ren Zhenglai/XinHua/Xinhua

Press/Corbis

In fact the Chinese artist and activist has modelled his entire output and approach to life on Duchamp's example. He, like the Frenchman, is at the centre of his own universe: fearless and determined, an artist whose own readymades are also often superficially playful but contain profound questions and statements. He too makes assisted readymades, which in Ai Weiwei's case often begin with 4,000-year-old neolithic Chinese pottery vases, ancient and revered objects which he then decorates in gaudy modern colours, or sometimes with the Coca-Cola logo.

On one occasion he thought it would be amusing to take a series of photographs of himself dropping one of these vases on to a concrete floor – to record the moment when it smashed. He duly did this and thought nothing more of it until an exhibition of his work was being assembled at an art gallery. The curator contacted him to say that they didn't have quite enough for the show and to ask if he had anything else. The artist had a rummage in his studio and came up with the photographs of the dropping of the vase. The images were then hung in the gallery under the title Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) and duly became a famous artwork. Which proved Ai Weiwei correct in his belief that his every action is part of his art, while also echoing an example of Duchamp retro-fitting, when he proclaimed that his bicycle wheel attached to the top of a stool was an assisted readymade, even though at the time he made it only as an amusement for himself.

It is Duchamp who is to blame for the whole "is it art?" debate – which was, of course, what he intended. It is because of Duchamp that Tracey Emin's unmade bed (My Bed, 1998) is a work of art and yours is not. But that is not to say that Emin's or any other artist's conceptually based work is necessarily worthy of our attention – each piece should be judged on its merits, as the American artist Sol LeWitt pointed out.

He wrote in an essay in 1967 that conceptual art is only good if the idea is good. And that you can decide for yourself.

Western star ... the ubiquitous ute, favoured transport in Broken Hill.

Elissa Blake takes an art-lover's tour of Broken Hill, with larger-than-life characters and even larger landscapes.

Western star ... the ubiquitous ute, favoured transport in Broken Hill.

Elissa Blake takes an art-lover's tour of Broken Hill, with larger-than-life characters and even larger landscapes.  The Broken Earth complex.

The locals say there is a sense of "spirit" in this country.

In the silence, the vastness of the landscape and the sky certainly put you in your

place. "I see the landscape as almost prehistoric," Ian Howarth says as he scans the 360-degree view of the scrubby plains bordered in the distance by the Barrier and Flinders ranges. "It's so weathered and worn. It carries the weight of aeons of time. It's almost the land that time forgot."

The Broken Earth complex.

The locals say there is a sense of "spirit" in this country.

In the silence, the vastness of the landscape and the sky certainly put you in your

place. "I see the landscape as almost prehistoric," Ian Howarth says as he scans the 360-degree view of the scrubby plains bordered in the distance by the Barrier and Flinders ranges. "It's so weathered and worn. It carries the weight of aeons of time. It's almost the land that time forgot."