New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, it's about time the UK's leading

institutions, such as London's National Gallery, presented modern art

alongside old masters

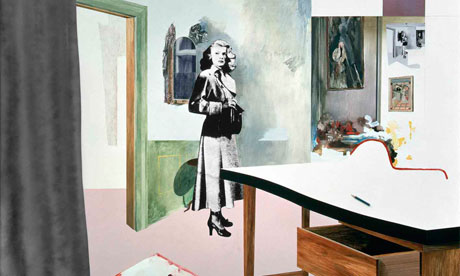

A Metropolitan approach … detail of painting by Richard Hamilton. Photograph: © Richard

A Metropolitan approach … detail of painting by Richard Hamilton. Photograph: © Richard

The first time I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art was like waking up in fairyland. There is no other museum quite like this palace of wonders on the east side of New York's Central Park. It magically brings together an ancient Egyptian temple, 18th-century salons and some of the greatest works of Rembrandt and Vermeer, among other delights, in airy, well-lit galleries with regular views of the tree-filled park.

Yet what truly marks this museum out from European cousins such as the Louvre and – until now – London's National Gallery is that it takes for granted a fact that still causes endless tensions in the UK: the rightful place of modern and contemporary art alongside the treasures of the past.

This season's big exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum is a survey of Andy Warhol's living artistic influence. This is not an unusual project for a museum whose permanent collection includes, as well as El Greco's View of Toledo, such modern American masterpieces as White Flag by Jasper Johns.

When I first visited New York, this easy intimacy of old and new transformed my view of art. In Britain, art fans have a habit of being dogmatic "conservatives" or "modernists". The Metropolitan Museum embodies a much richer way of seeing art: the new grows out of the old, the old is renewed by the visions of today.

But Brits may be about to become Americans, at least in the way we experience art. London's National Gallery is launching a quite new approach to the relation between art and its history. This museum whose permanent collection culminates around 1900 is adopting an approach that may even make the Metropolitan envious. Its director will be speaking at Frieze Masters, the new art fair from the makers of Frieze that claims to bring together old and new. The NG has thrown its weight behind this venture. Meanwhile, it is about to show the last works of Richard Hamilton and put on its first ever photography exhibition.

The problem with new art at the National Gallery used to be that its contemporary exhibitions seemed either tacked-on or critically naive. The new, sophisticated approach can only be good for this gallery, and good for art.

I hope the season of Frieze Masters sees a truly civilised art culture finally arrive in Britain. You might almost say, a Metropolitan way of seeing.

A Metropolitan approach … detail of painting by Richard Hamilton. Photograph: © Richard

A Metropolitan approach … detail of painting by Richard Hamilton. Photograph: © Richard The first time I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art was like waking up in fairyland. There is no other museum quite like this palace of wonders on the east side of New York's Central Park. It magically brings together an ancient Egyptian temple, 18th-century salons and some of the greatest works of Rembrandt and Vermeer, among other delights, in airy, well-lit galleries with regular views of the tree-filled park.

Yet what truly marks this museum out from European cousins such as the Louvre and – until now – London's National Gallery is that it takes for granted a fact that still causes endless tensions in the UK: the rightful place of modern and contemporary art alongside the treasures of the past.

This season's big exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum is a survey of Andy Warhol's living artistic influence. This is not an unusual project for a museum whose permanent collection includes, as well as El Greco's View of Toledo, such modern American masterpieces as White Flag by Jasper Johns.

When I first visited New York, this easy intimacy of old and new transformed my view of art. In Britain, art fans have a habit of being dogmatic "conservatives" or "modernists". The Metropolitan Museum embodies a much richer way of seeing art: the new grows out of the old, the old is renewed by the visions of today.

But Brits may be about to become Americans, at least in the way we experience art. London's National Gallery is launching a quite new approach to the relation between art and its history. This museum whose permanent collection culminates around 1900 is adopting an approach that may even make the Metropolitan envious. Its director will be speaking at Frieze Masters, the new art fair from the makers of Frieze that claims to bring together old and new. The NG has thrown its weight behind this venture. Meanwhile, it is about to show the last works of Richard Hamilton and put on its first ever photography exhibition.

The problem with new art at the National Gallery used to be that its contemporary exhibitions seemed either tacked-on or critically naive. The new, sophisticated approach can only be good for this gallery, and good for art.

I hope the season of Frieze Masters sees a truly civilised art culture finally arrive in Britain. You might almost say, a Metropolitan way of seeing.

No comments:

Post a Comment